17th September 2022

Fill in the blanks

Karnali River, NPL

An ascent equal to the descent down to meet the river of Karnali began from Belkhet. For the first half, the trail ran up swirling road tracks, after that it went through a forest, before meeting a straight track by whose side hundreds of felled trees lay. My mood for some reason was geared towards giving things a closer look that morning. One of the trees had survived through fifty two winters without much turmoil; the rings on the log spiraled even, in its afterlife, little cracks had webbed and widened delivering a work of art, a work of death. On another fallen log, a sprout had emerged of colors red and lime, shaped like a heart, calling for mercy with its shadow. The birds had stopped singing. The road track raced straight, it had little time to listen or learn. From one edge of the hillside, the road curved and went towards the hill that could be seen on the opposite side. It led to a man sleeping amidst disregarded Panchadeval structures, one of which had met dust, in the village of Binayak. One foot crossed over another, his face concealed by a cap, hands inside the pockets of his jacket, he rested on the desecrated temple abandoned by gods, immune to the pains of the world. I had lunch, the usual daalbhaat, at a roadside shack. Some snappy young men were deeply engaged in a game of carom board right outside. I wondered if the woman, whose head was covered, who was busy preparing and serving meals at the shack, ever got to play the game.

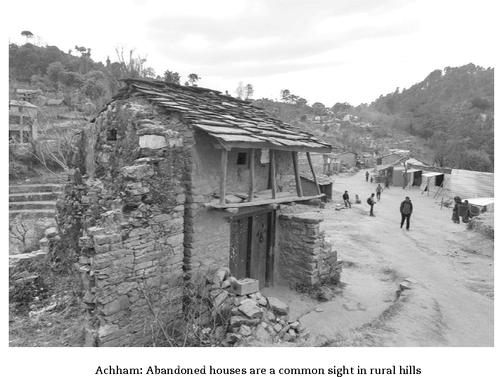

For hours after that, the strip was of a mundane nature and demanded persistence. Highways are built to create efficient connections; they elude vibrant communities and foster the creation of gray ones instead. Until I reached the outskirts of Mangalsen, except for the time when a black tempo roared past me, my concentration remained unhindered. An elderly woman, holding her grandchild tight, greeted me. She could only speak in the vernacular, but we did manage to fill in the blanks with expressions and understand each other. With an infectious smile, she asked me to take a picture of them, which I gladly did. “Such a warm welcome to the town” I said to myself. I went down to the main market with the setting sun, inquiring about budget lodges. I reached the town‖s most prominent landmark, the old palace. Several city residents had gathered in that open area to watch the sunset; it had become an ideal site for people from all walks of life, particularly youngsters, to come together and unwind. The palace, which was almost a century and a half old (the ruins upon which the palace had been built were much older) had been bombed to smithereens by the Maoists during the conflict. It glowed bright in aggravation – a miserable stack of bricks awaiting a genuine reconstruction effort. The name of the town itself had been derived from the temple of Mangalseni Bhagwati that the palace had housed in an earlier epoch. The dilapidation that afflicted such structures marked a loss of soul. I met two young men there and had a pleasant exchange with them. They were kind enough to lead me to the main town junction and help fix a lodge for me. It was as basic as I wanted arrangements to be and so was the price. I shared the room with a couple of noisy boys who had come from a nearby village to explore the town. The lodge owner warned me to stay wary of them. I did not have secret pockets or other measures of security and so decided to place faith on luck instead.